Hi Everybody!!

My happy (not flappy) birds of 2 days ago turned out to be flappy birds after all: they are gone. They left last night with thousands of other birds. I heard birds flying over loud and fast for about 10 minutes. All different kinds sounded to be flying together as I heard geese, ducks, blackbirds and the little birds like goldfinch. Then there was quiet and stillness. Now all of these birds were not here, but as mine are gone, they left when the others passed over. I knew it was getting close as they leave every year. This year it was after the full snow moon of February so there was plenty of light for the night riders. Why do they leave the wonderful home in the south? It is time for birds to breed and they return to the breeding grounds. The pantries have been restocked with fresh bugs and grasses for spring. Below I have shared info excerpt on bird migration from the Wikipedia page. Please see link for complete report. Your photostudy will be the last American Goldfinch photos until next Christmas. Enjoy!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bird_migration

Bird migration

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

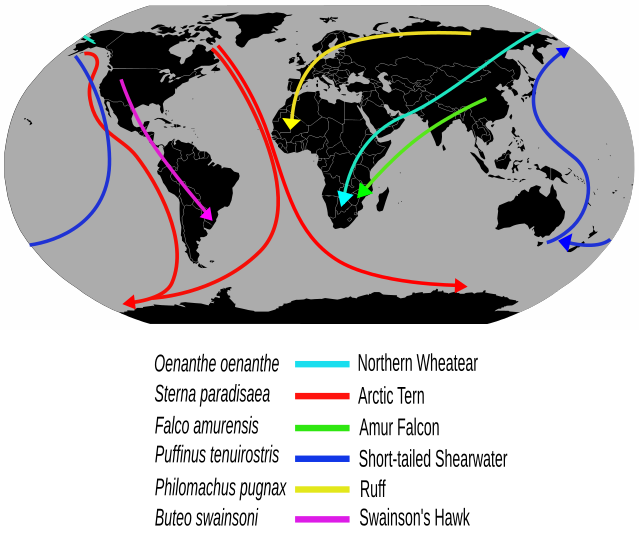

Bird migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south along a flyway between breeding and wintering grounds, undertaken by many species of birds. Migration, which carries high costs in predation and mortality, including from hunting by humans, is driven primarily by availability of food. Migration occurs mainly in the Northern Hemisphere where birds are funnelled on to specific routes by natural barriers such as the Mediterranean Sea or the Caribbean Sea.

Historically, migration has been recorded as much as 3,000 years ago byAncient Greek authors including Homer and Aristotle, and in the Book of Job, for species such as storks, Turtle Doves, and swallows. More recently, Johannes Leche began recording dates of arrivals of spring migrants in Finland in 1749, and scientific studies have used techniques including bird ringing and satellite tracking. Threats to migratory birds have grown with habitat destruction especially of stopover and wintering sites, as well as structures such as power lines and wind farms.

The Arctic Tern holds the long-distance migration record for birds, travelling between Arctic breeding grounds and the Antarctic each year. Some species of tubenoses (Procellariiformes) such as albatrosses circle the earth, flying over the southern oceans, while others such as Manx Shearwaters migrate 14,000 km (8,700 mi) between their northern breeding grounds and the southern ocean. Shorter migrations are common, including altitudinal migrations on mountains such as the Andes and Himalayas.

The timing of migration is controlled primarily by changes in day length. Migrating birds navigate using celestial cues from the sun and stars, the earth's magnetic field, and probably also mental maps. Migration has developed independently in different groups of birds and does not appear to require genetic change; some birds have acquired migratory behaviour since the last ice age.

File:Migrationroutes.svg

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Size of this preview: 639 × 600 pixels. Other resolutions: 256 × 240 pixels | 511 × 480 pixels | 818 × 768 pixels | 1,091 × 1,024 pixels | 1,500 × 1,408 pixels.

Original file (SVG file, nominally 1,500 × 1,408 pixels, file size: 253 KB)

General patterns[edit]

Migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south, undertaken by many species of birds. Bird movements include those made in response to changes in food availability, habitat, or weather. Sometimes, journeys are not termed "true migration" because they are irregular (nomadism, invasions, irruptions) or in only one direction (dispersal, movement of young away from natal area). Migration is marked by its annual seasonality.[1] Non-migratory birds are said to be resident or sedentary. Approximately 1800 of the world's 10,000 bird species are long-distance migrants.[2]

Many bird populations migrate long distances along a flyway. The most common pattern involves flying north in the spring to breed in the temperate or Arctic summer and returning in the autumn to wintering grounds in warmer regions to the south. Of course, in the Southern Hemisphere the directions are reversed, but there is less land area in the far South to support long-distance migration.[3]

The primary motivation for migration appears to be food; for example, some hummingbirds choose not to migrate if fed through the winter. Also, the longer days of the northern summer provide extended time for breeding birds to feed their young. This helps diurnalbirds to produce larger clutches than related non-migratory species that remain in the tropics. As the days shorten in autumn, the birds return to warmer regions where the available food supply varies little with the season.[citation needed]

These advantages offset the high stress, physical exertion costs, and other risks of the migration such as predation. Predation can be heightened during migration: the Eleonora's Falcon, which breeds on Mediterranean islands, has a very late breeding season, coordinated with the autumn passage of southbound passerine migrants, which it feeds to its young. A similar strategy is adopted by the Greater Noctule bat, which preys on nocturnal passerine migrants.[4][5][6] The higher concentrations of migrating birds at stopover sites make them prone to parasites and pathogens, which require a heightened immune response.[3]

Within a species not all populations may be migratory; this is known as "partial migration". Partial migration is very common in the southern continents; in Australia, 44% of non-passerine birds and 32% of passerine species are partially migratory.[7] In some species, the population at higher latitudes tends to be migratory and will often winter at lower latitude. The migrating birds bypass the latitudes where other populations may be sedentary, where suitable wintering habitats may already be occupied. This is an example of leap-frog migration.[8] Many fully migratory species show leap-frog migration (birds that nest at higher latitudes spend the winter at lower latitudes), and many show the alternative, "chain migration" where populations 'slide' more evenly North and South without reversing order.

Within a population, it is common for different ages and/or sexes to have different patterns of timing and distance. FemaleChaffinches in Eastern Fennoscandia migrate earlier in the autumn than males do.[9]

Most migrations begin with the birds starting off in a broad front. Often, this front narrows into one or more preferred routes termedflyways. These routes typically follow mountain ranges or coastlines, sometimes rivers, and may take advantage of updrafts and other wind patterns or avoid geographical barriers such as large stretches of open water. The specific routes may be genetically programmed or learned to varying degrees. The routes taken on forward and return migration are often different.[3] A common pattern in North America is clockwise migration, where birds flying North tend to be further West, and flying South tend to shift Eastwards.

Many, if not most, birds migrate in flocks. For larger birds, flying in flocks reduces the energy cost. Geese in a V-formation may conserve 12–20% of the energy they would need to fly alone.[10][11] Red Knots Calidris canutus and Dunlins Calidris alpina were found in radar studies to fly 5 km per hour faster in flocks than when they were flying alone.[3]

Birds fly at varying altitudes during migration. An expedition to Mt. Everest found skeletons of Pintail and Black-tailed Godwit at 5000 m (16,400 ft) on the Khumbu Glacier.[12] Bar-headed Geese have been recorded by GPS flying at up to 6,540 metres while crossing the Himalayas, at the same time engaging in the highest rates of climb to altitude for any bird. Anecdotal reports of them flying much higher have yet to be corroborated with any direct evidence.[13] Seabirds fly low over water but gain altitude when crossing land, and the reverse pattern is seen in landbirds.[14][15] However most bird migration is in the range of 150 m (500 ft) to 600 m (2000 ft). Bird-hit aviation records from the United States show most collisions occur below 600 m (2000 ft) and almost none above 1800 m (6000 ft).[16]

Bird migration is not limited to birds that can fly. Most species of penguin migrate by swimming. These routes can cover over 1000 km. Blue Grouse Dendragapus obscurus perform altitudinal migration mostly by walking. Emus in Australia have been observed to undertake long-distance movements on foot during droughts.[3]

Long-distance migration[edit]

The typical image of migration is of northern landbirds, such as swallows and birds of prey, making long flights to the tropics. However, many Holarctic wildfowl and finchspecies winter in the North Temperate Zone, but in regions with milder winters than their summer breeding grounds. For example, the pink-footed goose migrates from Iceland toBritain and neighbouring countries, whilst the Dark-Eyed Junco migrates from subarcticand arctic climates to the contiguous United States[24] and the American Goldfinch from taiga to wintering grounds extending from the American South northwestward to Western Oregon.[25] Migratory routes and wintering grounds are traditional and learned by young during their first migration with their parents. Some ducks, such as the Garganey, move completely or partially into the tropics. The European pied flycatcher also follows this migratory trend, breeding in Asia and Europe and wintering in Africa.

The same considerations about barriers and detours that apply to long-distance land-bird migration apply to water birds, but in reverse: a large area of land without bodies of water that offer feeding sites is a barrier to may also be a barrier to a bird that feeds in coastal waters. Detours avoiding such barriers are observed: for example, Brent Geese migrating from the Taymyr Peninsula to the Wadden Sea travel via the White Sea coast and theBaltic Sea rather than directly across the Arctic Ocean and northernScandinavia.[citation needed]

A similar situation occurs with waders (called shorebirds in North America). Many species, such as Dunlin and Western Sandpiper, undertake long movements from their Arctic breeding grounds to warmer locations in the same hemisphere, but others such asSemipalmated Sandpiper travel longer distances to the tropics in the Southern Hemisphere. Like the large and powerful wildfowl, the waders are strong fliers. This means that birds wintering in temperate regions have the capacity to make further shorter movements in the event of particularly inclement weather.[citation needed]

For some species of waders, migration success depends on the availability of certain key food resources at stopover points along the migration route. This gives the migrants an opportunity to refuel for the next leg of the voyage. Some examples of important stopover locations are the Bay of Fundy and Delaware Bay.[26][27]

Some Bar-tailed Godwits have the longest known non-stop flight of any migrant, flying 11,000 km from Alaska to their New Zealandnon-breeding areas.[28] Prior to migration, 55 percent of their bodyweight is stored fat to fuel this uninterrupted journey.

Seabird migration is similar in pattern to those of the waders and waterfowl. Some, such as the Black Guillemot and some gulls, are quite sedentary; others, such as most ternsand auks breeding in the temperate northern hemisphere, move varying distances south in the northern winter. The Arctic Tern has the longest-distance migration of any bird, and sees more daylight than any other, moving from its Arctic breeding grounds to the Antarctic non-breeding areas. One Arctic Tern, ringed (banded) as a chick on the Farne Islands off the British east coast, reached Melbourne, Australia in just three months from fledging, a sea journey of over 22,000 km (14,000 mi). A few seabirds, such as Wilson's Petrel and Great Shearwater, breed in the southern hemisphere and migrate north in the southern winter. Seabirds have the additional advantage of being able to feed during migration over open waters.[citation needed]

The most pelagic species, mainly in the 'tubenose' order Procellariiformes, are great wanderers, and the albatrosses of the southern oceans may circle the globe as they ride the "roaring forties" outside the breeding season. The tubenoses spread widely over large areas of open ocean, but congregate when food becomes available. Many are also among the longest-distance migrants; Sooty Shearwaters nesting on the Falkland Islands migrate 14,000 km (8,700 mi) between the breeding colony and the North Atlantic Ocean off Norway. Some Manx Shearwaters do this same journey in reverse. As they are long-lived birds, they may cover enormous distances during their lives; one record-breaking Manx Shearwater is calculated to have flown 8 million km (5 million miles) during its over-50 year lifespan.[29]

Some large broad-winged birds rely on thermal columns of rising hot air to enable them to soar. These include many birds of prey such as vultures, eagles, and buzzards, but alsostorks. These birds migrate in the daytime. Migratory species in these groups have great difficulty crossing large bodies of water, since thermals only form over land, and these birds cannot maintain active flight for long distances. Mediterranean and other seas present a major obstacle to soaring birds, which must cross at the narrowest points. Massive numbers of large raptors and storks pass through areas such as Gibraltar,Falsterbo, and the Bosphorus at migration times. More common species, such as theEuropean Honey Buzzard, can be counted in hundreds of thousands in autumn. Other barriers, such as mountain ranges, can also cause funnelling, particularly of large diurnal migrants. This is a notable factor in the Central American migratory bottleneck. Batumi bottleneck in the Caucasus is one of the heaviest migratory funnels on earth. Avoiding flying over the Black Sea surface and across high mountains, hundreds of thousands of soaring birds funnel through an area around the city of Batumi, Georgia.[30] It has been suggested [31] that birds of prey (such as Honey Buzzards) which migrate using thermals may benefit from losing 10 to 20% of their weight and that this may explain why they forage less on migration than do smaller birds of prey with more active flight such as Falcons, Hawks and Harriers.

Many of the smaller insectivorous birds including the warblers, hummingbirds andflycatchers migrate large distances, usually at night. They land in the morning and may feed for a few days before resuming their migration. The birds are referred to as passage migrants in the regions where they occur for short durations between the origin and destination.[32]

Nocturnal migrants minimize predation, avoid overheating, and feed during the day.[17]One cost of nocturnal migration is the loss of sleep. Migrants may be able to alter their quality of sleep to compensate for the loss.[33]

Short-distance and altitudinal migration[edit]

Many long-distance migrants appear to be genetically programmed to respond to changing day length. Species that move short distances, however, may not need such a timing mechanism, and may move in response to local weather conditions. Thus mountain and moorland breeders, such as Wallcreeper and White-throated Dipper, may move only altitudinally to escape the cold higher ground. Other species such as Merlin and Skylarkwill move further to the coast or to a more southerly region. Species like the Common Chaffinch are not migratory in Britain, but move south or to Ireland in very cold weather.[citation needed]

Short-distance passerine migrants have two evolutionary origins. Those that have long-distance migrants in the same family, such as the Common Chiffchaff, are species of southern hemisphere origins that have progressively shortened their return migration to stay in the northern hemisphere.[34]

Species that have no long-distance migratory relatives, such as the waxwings, are effectively moving in response to winter weather and the loss of their usual winter food, rather than enhanced breeding opportunities.[35]

In the tropics there is little variation in the length of day throughout the year, and it is always warm enough for a food supply (although because of competition, there may not be enough food for every bird). Migration within the tropics has been far less studied than in the temperate zones. It was once assumed that tropical birds were mostly sedentary; however, altitudinal migration and other within-tropics movements appear to be surprisingly common.[citation needed] Many tropical regions have wet and dry seasons, inducing some birds to migrate or wander widely to find food. Indeed, the monsoons of India are preceded by the arrival of the Jacobin Cuckoo, the "harbinger of the monsoon". Other examples include the Woodland Kingfisher of west Africa and many Australian birds.[citation needed]

There are a few species, notably cuckoos, which are genuine long-distance migrants within the tropics. An example is the Lesser Cuckoo, which breeds in India and spends the non-breeding season in Africa. Such examples help make the case that food supplies, not weather per se, drive migration patterns.[citation needed]

Altitudinal migration is common on mountains worldwide, such as in the Himalayas and the Andes.[36] Quite often, altitudinal migration is combined with distance migration; for example, the Himalayan Kashmir Flycatcher and Pied Thrush both move as far south as the highlands of Sri Lanka. Altitudinal migration may even be important to birds living on relatively small islands, such as the Hawaiian Islands, which have high mountains.[citation needed]

Rainbow Bee-eater

Threats and conservation[edit]

Human activities have threatened many migratory bird species. The distances involved in bird migration mean that they often cross political boundaries of countries and conservation measures require international cooperation. Several international treaties have been signed to protect migratory species including the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 of the US.[73] and the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement[74]

The concentration of birds during migration can put species at risk. Some spectacular migrants have already gone extinct, the most notable being the Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius). During migration the enormous flocks were a mile (1.6 km) wide, darkening the sky and 300 miles (480 km) long, taking several days to pass.[75]

Other significant areas include stop-over sites between the wintering and breeding territories.[76] A capture-recapture study of passerine migrants with high fidelity for breeding and wintering sites did not show similar strict association with stop-over sites.[77]

Hunting along the migratory route can also take a heavy toll. The populations of Siberian Cranes that wintered in India declined due to hunting along the route, particularly in Afghanistan and Central Asia. Birds were last seen in their favourite wintering grounds in Keoladeo National Park in 2002.[78]

Structures such as power lines, wind farms and offshore oil-rigs have also been known to affect migratory birds.[79] Habitat destruction by land use changes is the biggest threat, and shallow wetlands that are stopover and wintering sites for migratory birds are particularly threatened by draining and reclamation for human use.

link to photostudy in G+ Album:

https://plus.google.com/u/0/photos/117645114459863049265/albums/5981013876669336529

...this is brendasue signing off from Rainbow Creek. See You next time!

GOODBYE GOLDIES!

O+O

No comments:

Post a Comment

Hi Everybody! Please say hello and follow so I know you are here! Due to the inconsideration of people trying to put commercials on my blog comment area, I have restricted use of anonymous posts. Sorry that some hurt all.

My public email is katescabin@gmail.com No spammers or trolls